Musings

To David Eby: These Conversations Must Continue

I was invited on Tuesday morning on to do a CBC Radio studio interview. The invitation was extended because of an email I had sent objecting to the framing of the reaction to Ms. Robinson’s hateful rhetoric as the Muslim community’s issue with her remarks.

I had also published a blog post demanding Ms. Robinson’s resignation, which I believe was another reason the show asked me to appear. Once the news broke that Ms. Robinson had resigned from cabinet, CBC Radio uninvited me. I was told the show’s producers had decided to pivot to another angle.

I’m not going to question the merit of the show’s decision although I was disappointed to lose the opportunity to contribute to a broader public conversation.

Since I was denied the opportunity to share my thoughts on air, I would like to take the time to share a few of my thoughts with you here.

There are three points I’d like to bring to your attention:

1. Ms. Robinson is out of cabinet, but it took a significant amount of community action, a lot of protest, and a general sense of alarm for you, David Eby, to act. It took too long.

What the delay indicates to me, is that there’s a lot of work that you need to do on your own education regarding Palestinian history, the grave injustices that have marked the last 75 years of occupation, and the terrible human cost that we are witnessing every moment of every day.

Ms. Robinson’s resignation, this one outcome, cannot be seen as an ending. It’s just the start of a process in rediscovering empathy, enhancing understanding, and recognizing the value of Palestinian lives, past, present, and future.

2. Ms. Robinson has held the portfolio as Minister of Post-Secondary Education and Future Skills for a while now. Given that her remarks have now exposed her ideological biases, it’s essential for you to investigate the decisions she has made while in that position to ensure that racism and Islamophobia did not play a part in any policy or operational decision that she initiated, made, and implemented.

3. The issue of what is happening in Palestine, both in Gaza and throughout the West Bank, is greater than whether Ms. Robinson has left cabinet. As such, these conversations must continue, and the dialogue can’t just be about pivoting to discuss the fact that Ms. Robinson is no longer a Minister and what that means for you, your government, and your re-election prospects.

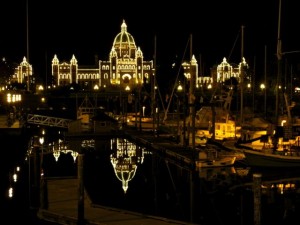

BC Legislature, Victoria, BC

Oh, and one more thing before I go.

Those attempting to excuse Ms. Robinson’s remarks as a mistake, or those attacking the individuals demanding her resignation, are wrong. Ms. Robinson’s remarks were not a mistake, and she is not the subject of a vendetta.

People reacted to the evidence of her ingrained beliefs, a revelation to some and for those who have been following the breadcrumbs on her social media trail, a confirmation of a deeply unsettling behaviour pattern.

As I drove to work on Tuesday, anticipating that the invitation I had received earlier that morning would be withdrawn if your afternoon announcement included the news of Ms. Robinson’s resignation, I listened to the noon show on CBC.

The host read an email from a listener who explained her contention that Ms. Robinson did not need to resign by writing that all humans are equal.

That’s precisely the point. All humans are equal and as such deserve the rights and dignities afforded to people such as Ms. Robinson, the email writer herself, and you. Palestinians are humans, too, and nothing is more important at this time then advocating for their right to live in peace and to act when others treat them as disposable, erase them from history, and deny the truth of their existence.

To Selina Robinson: Resign Now

How dare you Selina Robinson!

How dare you take one part of history to erase another!

Do you know how clearly you’ve demonstrated your own ignorance by spouting the hateful rhetoric that Palestine was “a crappy piece of land with nothing on it”?

How dare you annihilate the memory, lives, and legacies of “several hundred thousand people” with a shrug of your shoulders as if they were no more than a few motes of dust to brush off the sleeve of your jacket!

How dare you assert that the land of Palestine was there for colonial powers to offer up to others as a plum reward! As if it were their right to give away land they had forcibly occupied. To treat the land as a token that they could forfeit in a high stakes’ poker game.

Do you even know that Zionist leaders considered other parts of the world before settling on Palestine as the one that was theirs to seize as a homeland?

How dare you deny the history and experience of people such as my grandfather and grandmother! They had productive lives in Haifa until 1948 when Israel’s expansionist march through and over people’s existence forced them to flee to Lebanon! My grandmother narrowly escaped a sniper’s bullet and my grandfather had to give up everything, leaving behind all he had built up through his professional career as a civil engineer.

My grandparents lost everything, and they were among the fortunate who had a place to go. They could return to the Lebanese village they were born in, unlike the many who were forced to live in refugee camps, left stateless, left to dream of the homes that were once theirs and denied the right to return to the homes now occupied by settlers who displaced them.

How dare you imply that my grandparents’ lives were nothing! How dare you deny the reality of all other Palestinian lives, of people who lived in Palestine with family trees rooted in the fertile soil that extended back not decades or years, but centuries!

How dare you deny a culture of a people, a history of a population, the lives of mothers, fathers, sons, daughters, children, aunts, uncles, cousins, grandmothers, grandfathers, friends, relatives and loved ones who shared and continue to share traditions, customs, music, art, poetry, craft, food, and who nourished the lands they tilled and harvested!

How dare you deny the productive labour that created a land that was given away because it was desirable and wanted and envied!

How dare you mythologize the moral superiority and inherent worth of one group of people to rationalize the deaths of over 25,000 souls, injuries to over 65,000 human beings, and the catastrophic destruction of hospitals, homes, playgrounds, schools, and universities, such places of learning as you are responsible for here!

How dare you legitimize the trauma that will mark generations to come! How dare you support undermining the rule of law, ignoring the International Court of Justice, and rendering international order virtually meaningless!

How dare you claim the authority to sit as a representative of the people in the BC Legislature, let alone as Minister of Post-Secondary Education and Future Skills, when your comments today displayed your own lack of education, your tenuous understanding of the facts, your ideological bias, your indisputable racism, and your utter lack of humanity!

How dare you!

Resign.

Now.

Reema Faris

cc. David Eby

Remembering Uncle P. – A Tribute

I don’t know how to do it.

I don’t know how to understand a world that no longer has Uncle Pethro in it.

It’s not that I’m overwhelmed with grief at his passing. Losing my mother eight years ago shifted my perspective on death and dying. So, I am sad, I am heartbroken, I am bereft, but I am not in pieces.

Still, the journey of saying a final goodbye to someone who has been a constant fixture in my life is difficult. Coming to terms with the impact his loss has on others is even more fraught with emotions.

The formal obituary tells the story of Uncle Pethro’s life and outlines the legacies of his accomplishments, achievements, and successes. It pays tribute to his extended and extensive family and honours the woman who stood by his side over six decades, matching him stride for stride over the years, my Aunt Madge.

But who was this man to me?

My mother’s first cousin and one of her best friends. Uncle Pethro and my mom shared a bond that helped each of them triumph over the reality of being outsiders. Others consigned them to the margins. They asserted their right to be at and in the centre. They made sure they were seen, heard, and recognized without compromising what they stood for and who they wanted to be. They did not accept the spaces others relegated them to and forged their own paths, carved out more imaginative lives, lived bigger stories than the ones others wrote for them.

Uncle Pethro was the man who would say, “Let me look at you!” even if you were standing right in front of him. He didn’t just want to see the face you presented to the world, he wanted to see the essence of who you were on the inside.

He was also the man with the all-consuming embrace. The man whose arms would wrap around you and make you feel protected, invincible, and treasured.

He was the man whose voice echoed in the room, whose voice was deep, resonant, and full. And — I say this with love — it’s a voice you heard often and at length because he loved to pontificate! He wanted to dig out the complexities of life, to talk about its nuances, to sort out its chaotic randomness at the same time that he could be rude, crude, and indelicate.

He was the man who had a pride of place. He loved Jamaica, the land of his birth, in all its contradictions, even if it was the home he had to leave to find the space to be free and to become the man he wanted to be.

He was generous, caring, and thoughtful, opening his doors, at home and at work, to a diversity of folk. He and Aunt Madge entertained well and often, and they set a standard as hosts that is difficult to achieve, and essential to emulate.

We all forgave Uncle Pethro his bombastic nature because underneath it all beat a passionate, life-full, and cheery heart.

Until it didn’t.

Ultimately, it was Uncle Pethro’s body that stopped working with him and started to work against him, that whittled away at him.

He was stalwart throughout each health crisis that battered him. His physical strength and mental toughness, along with Aunt Madge’s love, diligence, and care, carried him further and for longer than seemed possible.

When I moved to Toronto in 1986, Uncle Pethro and Aunt Madge welcomed me into their home and made sure I never felt alone in the vastness of the city or lost in the gulf of the choice I had made when I left home.

They saw me through the ups and downs of my time in that city, celebrated with me when things went well and consoled me when they did not. We shared food, drink, and conversation. We built a bond that transcended the familial connection. That feeling of being a part of each other’s lives became even stronger after I returned to Vancouver and our visits, because of the distance, became occasional rather than frequent.

Having spent the last few days in Toronto with Aunt Madge and the family, I’ve been reflecting on the past and ruminating on the future. Now I’m sitting here in seat 2B on Porter Air, Flight 309, surrounded by strangers, high above the clouds, and anxious to get home. I’m trying to make the pictures in my mind, of the vibrant, vital person I knew and loved, more animated and I’m fighting the way I feel that they are blurring and ebbing already. I’m trying to understand this new world that has lost that singular gravelly voice, that strong embrace, that hearty appetite, that appreciation for beauty, and that gift of laughter.

It’s not about making a saint out of my Uncle Pethro or remembering him as a paragon of virtue. It’s about knowing to love him as the man that he was.

Because if there’s anything I’ve learned from the years of being in Uncle Pethro’s company, is that to be human is divine even if we are flawed and our lives are finite.

To understand this world without Uncle Pethro is to understand that it was better with him in it, and that it will still be good because he was once a part of my mornings and my days, my nights, my years, my joys and my sorrows.

I will remember him.

Rest in peace Uncle Pethro.

Walk good.

Fragments of a Whole Being Belonging

I belong to Air Canada.

In this moment. January 2020.

Buckled into Seat 14C.

Far above where birds take flight. The place where dreams alone can live.

In this moment, I belong to this unbounded world above the clouds. A creature of the air.

This air-borne liberation is a mirage.

I know my feet belong on the ground. A creature of the earth.

I am on a flight to Montreal to visit friends. Their relocation to this city will bring me back again and again because our friendship is long standing and we will nurture it. My friends have also made me belong to Montreal again.

Again, because this is the city where my parents met. Where I was born, but never lived in for long. What part of me, then, belongs here? Belongs to this city where I speak the language only to a moderate level of fluency? Because all of me would not be if it weren’t for this city.

But countries and cities pull at me from all different directions.

Jamaica – my mother’s birthplace. Lebanon – my father’s. Kuwait – where my sister was born. Calgary – where my youngest sister was born. And Vancouver where we settled in 1974 and where my family has stayed since. All of us have ventured afar over the years, whether alone or together, to travel or to live for fragments of time. Toronto – where I lived for six years.

My whole being is a mosaic of spaces, places, and time. Of different cultures and societies. I identify with all of them and I identify with none of them. I am rooted in my experiences with each and am unrooted because I do not feel like I wholly belong in any of them.

They have all shaped me as have other cities I’ve visited, especially those that feel as if they are the locations where I ought to be, where I yearn to be.

In Montreal, my friends and I go to a movie they want to share with me. Their second viewing, my first.

Antigone (in French, Canada, 2019). Sophie Deraspe’s screenplay and her direction. Based on the Ancient Greek play by Sophocles. A play I know. A play that belongs to me because I have studied it, absorbed it, discussed it, taught it, remember it.

This film, this Antigone, which now belongs to me, too, tells the story of an immigrant family to Canada. Two girls, two boys, and a Grandmother, haunted by the memories of the children’s parents murdered in Algeria, in the country that they once belonged to.

In this country, this foreign Canada, do they belong?

Ismène, the older girl, has built a successful career as a hair stylist. The grandmother cooks, cleans, loves each child ferociously. Antigone is fearlessly devoted to the family, to their story, to their truth. In an address to her class, “une exposition,” she elevates her classmates from a state of boredom, heads on the desk, eyes rolling, to whip-straight postures, eyes that pierce through teenage school inertia. Her story of survival, loss, and grief lures them to listen.

Antigone’s two brothers? Étéocle and Polynice? The fierce family love envelops the two brothers and yet they search for belonging elsewhere.

Why isn’t their family enough?

And why do men so often find belonging in violence, especially vulnerable men?

The story of this dislocated, relocated family unravels in flashbacks and in real time. Antigone’s knowledge of her brothers, the appearance of their being and belonging, is contradicted by the reality she grasps in hindsight.

She remembers a night. Polynice creeps home late, after dark. He opens the fridge door, she startles him in the kitchen. He stands in the shadows, the pale light casting an eerie halo around him. Bruised, bloodied, black-eyed, he exults to his sister “I’m in,” “I’m in.”

In what? In toxic brotherhood? In a position to provide for his family now? In hopelessness? In power? In control, as illusory as that power and control may be?

Polynice is not a lone wolf. What he decides matters. It affects him, his brother, his sisters, his grandmother, his community. But he makes choices as if he were alone. Is his choice a resistance to belonging to this family or is it his way to belong more meaningfully?

His choice is made as if he were an island. But no person is an island.

As much as we may long for separation, for isolation. Long to escape duties, obligations, chores, stress, news, disasters, worries, fears. But a hermetic existence is possible for only a few, it is life’s answer or life’s purpose for even fewer.

Most of us, the vast majority, need – crave – connection. We are social creatures. Socialized creatures. We achieve our potential by being a part of a world wide web and I do not mean losing ourselves in the emptiness of cyberspace or discarding hours of our life on the internet.

We want to belong. We are part of a world of belonging.

We recognize that we are as others are. Lost, found, lonely, together, alive, dying, needy, giving, angry, happy, sad, joyful, cruel, kind, hateful, loving, powerful, powerless, smart, stupid, healthy, sick, caring, selfish, playful, serious, studious, ignorant, ambitious, lackadaisical, safe, unsafe, privileged, oppressed, worried, carefree, careful, careless, faithful, faithless, believing, unbelieving. Free, not free.

Isolation, being alone, is a desire, a fantasy, as is belonging. The former is a choice, the latter inescapable. We are compelled into connection. We are born into a web of connections.

We have to negotiate with ourselves as much as with others. We negotiate with life, with experiences. And despite this we are often unprepared for what life throws at us.

Perhaps there is a toxic underpinning to the idea of belonging. After all, embedded in the word “belong” is the idea of ownership. My husband, my wife, my spouse, my daughter, my son, my child, my father, my mother, my parents, my sister, my brother, my siblings, my niece, my nephew, my uncle, my aunt, my grandparents, my cousins, my relatives, my friend, my colleague, my acquaintance, my pet, my community, my neighbourhood, my job, my school, my work, my career, my money, my dreams, my aspirations, my humour, my loss, my grief, my beliefs, my body, my pain.

Would we be better served by leaving belonging to refer to objects? When we talk about humans, living creatures, plants, trees, the earth and the webs of existence in which we’re enmeshed, would it be better use other verbs: “connect,” “embrace,” “cherish,” “know,” “love”? I connect with this city; this city connects with me. This family embraces me; I embrace this family. These friends cherish me; I cherish these friends. I know that person; that person knows me. You love me; I love you.

Words alone will not remake belonging. We need to excavate the purpose, the meaning, the appeal, the allure, the temptation of belonging.

Why do we care about belonging? Why do we need to belong?

Where do we belong? To whom do we belong?

Where do I belong? To whom do I belong? Who belongs with me, to me?

I think we can only remake belonging if we learn to transcend the boundaries of belonging and not belonging. To embrace the ambiguity and uncertainty of embodying different states and ways of being. To be unbounded. To imagine our lives as bigger than what we can see, hear, touch, taste, and smell. Bigger than our dreams, bigger than our imaginations.

Bigger than our communities of “same as me.”

As big as our hearts.

Because we belong nowhere and everywhere.

I belong nowhere and everywhere.

I may live in Vancouver, but fragments of me are dispersed. Unless I identify with everywhere, I can’t care about the world, the environment, the fragile state of humanity’s existence.

We belong to nothing and everything.

I belong to nothing and everything.

Because I am not beholden or enthralled by a particular thing or person and yet I am curious about all the world has to offer.

We belong to no one and everyone.

I belong to no one and everyone.

Because I am not an object to be owned and yet I am human as you are human, as he is human, as she is human, as they are human, as the many are human.

This heart belongs to those I love, but not as a thing for them to own.

It is a gift that says they are valued and valuable.

This soul is untethered in a state of un-belonging.

The essence of me is free.

You Are My Sunshine: Remembering

We shared a birthday.

Auntie Laila and me.

And every year, when March 29th rolled around, I would call her, or she would call me.

This year marks the final such exchange.

Auntie Laila died yesterday.

Just as her personality was larger than life, the impact she had on me is much larger than the quantifiable amount of time that we spent in each other’s company.

We’re also part of an extended family in a culture where the furthest relation is as close as your brother or your sister, your mother or your father.

Auntie Laila was married to my Uncle Ed who is in fact my paternal grandfather’s first cousin.

That gives you a sense of how distant we are from one another on the family tree.

However, when it comes to human connection, closeness defies measurement. You cannot measure love in metres, centimetres, and kilometres or miles, inches, and yards.

When it comes to family, to those we love, distance is only every measured in heartbeats, thoughts, and dreams. If you think of a person, then they are with you. If you dream of a person, then they are with you. And when such a person dies, they never leave you.

The strength of the tie between Aunt Laila, her daughter Medina, my mother, and my sisters can be traced to a particular time and place.

We were living in Beirut in the early 1970s when Aunt Laila and Medina came to visit. In my memories, my father wasn’t there. He worked in Kuwait and was typically home for only one week every month or so.

This must have been one of the times he was away. The task of entertaining and touring fell to my Mom who at the time drove a red, four-door Peugeot. We crammed into the car, all six of us, for whichever excursion Mom and Auntie Laila had dreamt up. We would pass the time in conversation, laughter, and with music. In particular, a song.

“You are my sunshine, my only sunshine …”

Whether careening around the streets of Beirut or driving up to Karoun, the family village in the Bekaa Valley, we’d sing loudly and exuberantly with Auntie Laila leading the choir as the minutes ticked by on the clock and the kilometres of asphalt flowed under the tires.

“You make me happy when skies are gray …”

From that point on, Auntie Laila and my mother were sisters and whenever they were together they would gossip, they would giggle, they would laugh out loud. They supported one another, they travelled together, and they cooked for everyone.

When Mom died in 2015, Auntie Laila was unable to travel to Vancouver for the celebration of life, but she was in that room with us all.

She was there.

Knowing that Auntie Laila’s illness was advancing, and with the loss of another family matriarch that year, I was overwhelmed with the need to see her.

To hug her. To hear her say “Ya aini, ya habibti…”. My eyes, a profound endearment in Arabic, my dear one.

So, Luc and I did just that. We went to see Auntie Laila.

We embarked on a three-week road trip that took us from Vancouver to Kamloops, Jasper, Grande Prairie, Edmonton, Calgary, Lake Louise, Kelowna, and back home. At many stops along the way, we spent time with friends and family members. And in Grande Prairie, we caught up with Auntie Laila and the many relatives there.

It was magical.

“You’ll never know dear, how much I love you

Please don’t take my sunshine away …”

The last time I saw Auntie Laila in person was early December 2019.

I had suggested to my father that we visit Grande Prairie because the one truth that we continue to forget and have to relearn is that life — no matter how much we try to wrestle it to the ground — is random and change can come suddenly even when it seems like we will have forever. The toll of age and illness is never predictable. The time to go and see, to stop and call, to visit and reminisce is always now although it is not often feasible to follow through on such intentions and desires.

We were lucky enough to make plans and to act on them.

Dad and I travelled to Grande Prairie. As he challenged Uncle Ed to consecutive games of crib, I sat on the couch in the family room or in the living room and Auntie Laila sat in her chair. We would chat or not, we watched the Christmas movies playing on the television, or not. It didn’t really matter. What mattered is I could look up and see that she was there. I could smile at her, I could hug her, I could say, “I love you.”

The last time I saw Auntie Laila was just a few weeks ago on March 14th during a Zoom call that gathered households together from around the world to celebrate a number of family milestones.

Auntie Laila didn’t say anything, and she may not have quite understood what all the fuss was about, but just to see her made me tear up because while it felt as if she were in the room with me, she was so very far away.

“The other night dear, as I lay sleeping

I dreamt I held you in my arms …”

And now the connection has been disrupted.

There is comfort in the idea of Auntie Laila at peace, or more accurately — as my cousin Medina said to me on the phone today — she is somewhere cooking, shopping, laughing, gossiping, and partying up a storm with Alma, Haifa, Maza, and Yulanda among so many others.

It is, however, a cold comfort because the void she leaves behind is immense. It is now a distance that we will all only be able to traverse in our dreams, in our memories, and in our hearts.

In the stories we share with one another, over the years to come, of a woman who meant so very much to each and every one of us.

“But when I awoke, dear, I was mistaken

So I hung my head and I cried.”