Hierarchy And Assessment

The inaugural meeting of the new West Vancouver Board of Education will be held on December 13, 2011. On that date, I’ll be acknowledged as a Trustee and officially launched into my new role and new set of responsibilities.

In the lead up to that ceremony and the official recognition it entails, I also had the pleasure of meeting George Abbott, BC’s Minister of Education during his visit to the District earlier this week.

He met with the new Board for just over an hour for a very interesting, wide-ranging discussion touching on many of the key public education issues we are facing. He was thoughtful, approachable, keen to listen, and showed evidence of his personal commitment to his ministerial portfolio, one he’s held for approximately a year. He’s also got a very natural manner and a ready wit.

Minister Abbott’s visit was highly anticipated and a lot of planning went into making sure the day went smoothly. And while he struck me as very down-to-earth, I’m also aware that all the stops were pulled out for him and his team because of who he is.

In the lingo of our day, he is a Very Important Person.

As I have before, I found myself reflecting about the way we determine status in our society and the relative value of individuals. Think about the way we encourage our children to stand in line for autographs, to revere sports figures, to worship entertainers. In the case of anything related to Disney, those are line-ups for autographs from actors portraying characters. They aren’t real!

It seems to me we cannot escape the fact that we live in a very hierarchical system, one which by its very nature is inherently unfair. There are many inequalities in our society — economic inequality being one which served as the impetus for the Occupy movement — which we may find difficult to accept, which we may want to change, and which we may very well be stuck with for the foreseeable future.

My musing on hierarchy then morphed into thinking about the role of assessment in education. The connection was heightened because I happened to be in the midst of grading papers for the undergraduate course at SFU for which I serve as a Teaching Assistant.

My musing on hierarchy then morphed into thinking about the role of assessment in education. The connection was heightened because I happened to be in the midst of grading papers for the undergraduate course at SFU for which I serve as a Teaching Assistant.

Marking has proven to be the most challenging aspect of the job. I have no trouble discerning which papers are better than others — the quality of the content, the writing style, the technical skill, the way in which ideas and concepts have been distilled and discussed — but attributing a letter grade which will affect a student’s standing in the course and in their academic year is difficult. But I have to do it, I have to give them a mark.

From this experience, I understand more clearly why there is so much discussion — heartfelt, sincere, despairing, dismissive, agonizing — about assessment in elementary and secondary education.

Marks can act as barriers, as obstacles. They judge, they differentiate. They are subjective, they are unfair, they may not reflect the abilities, competencies, talents, and skills of the child. At the same time, are they not completely suited to the way we’ve structured our societal institutions? So, if one makes the argument for the elimination of letter grades, for doing away with academic honours, are we in fact doing a disservice to our students? If they are schooled in an environment which reflects a world we’d like to see — peer-based and egalitarian — do we set them up for disappointment when they are exposed to the world as it is?

It seems to me a chicken and egg situation: do we change education first in order to engineer changes in society or does society have to change first in order for the structure of the educational system to shift?

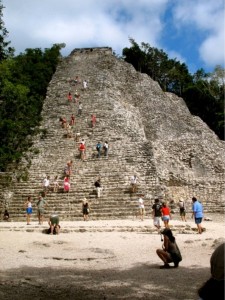

It’s a puzzle I look forward to thinking about and learning about because at the end of the day our goal is to help students achieve the most in their life (which may be defined in many different ways), to climb “to the top” of their potential, even perhaps to be Minister of Education one day.