Posts Tagged ‘marks’

Crazy Little Thing Called Twitter And The FSAs

At first I lurked.

I’d log on to Twitter.com and scroll through the streams, fascinated.

I started to tweet in support of my campaign during the 2011 civic election and now it’s part of my daily routine.

With Twitter, I keep an eye on my community. I get news from around the world. I read analyses of issues and events from different perspectives. I interact with well-known figures and people in faraway places, opportunities I may never have had otherwise.

Twitter is also ugly at times, “nasty, brutish, and short” in the words of Thomas Hobbes. And while it is liberating to talk to so many so easily, Twitter is also constraining.

Why?

My Twitter account is a mirror of who I am as a whole person, but that whole person includes being a public figure. I have to be aware that although I am speaking personally, some may mistakenly take my views as those of the West Vancouver Board of Education. I have to be aware that while I distinguish between the different hats I wear in life and the various roles I play, others may not.

Which brings me to the Foundation Skills Assessment (FSAs), a test administered to Grade 4 and Grade 7 students throughout British Columbia.

Twitter streams were on fire about the FSAs recently, but I kept mum. I felt that whatever I said in 140 characters could be mischaracterized.

Here’s some of what I wanted to say.

As a parent, I had no objection to my child writing the FSA. As a Trustee, I see value in the data collected because it can be used to align resources with demonstrated need.

Here’s the problem: what we want the FSA to do and what is done with the FSA results have diverged.

FSA data, in addition to use by the provincial government and by school districts, is used by a third-party organization to rank schools.

The Fraser Institute rankings are myopic: they claim to present an overall picture of a school, but the rankings seem to be unduly weighted on one factor, FSA scores.

Rather than the FSA, why not invest in developing literacy screeners for key grades, the results of which would be privately held and exclusively used by the school, the district, and the student’s family? I’m thinking of something like the early literacy screening used for kindergarten students in West Vancouver.

And while I acknowledge that provincial measures are needed for accountability purposes, perhaps a better method of tracking student performance could be determined through a consultative process with key partner groups.

Perhaps by separating the two requirements — diagnostic and reporting — and by creating mechanisms for each, we would be spared the yearly rankling spectacle of school rankings.

At our January public board meeting, Sandra-Lynn Shortall, District Principal – Early Learning, paraphrased a conversation she’d had with Dr. Stuart Shanker. “Early intervention,” she said, “is not the answer to helping students address their needs, rather it’s continuous intervention and connectedness.”

Just as Twitter is not always the best mode of communication, the FSA may not be the best mechanism to match vulnerable or struggling students with the continuing supports they need to succeed in our public education system.

I think we can do better.

Are Report Cards Irrelevant?

Report card bashing is a popular pastime these days in British Columbia. And the cacophony is bound to get louder when parents discover the report cards they receive bear little resemblance to what they usually get.

Imagine a parent standing there, hand outstretched expectantly for delivery of that all important document. The apprehensive child rummages around his or her backpack for the crumpled up envelope to deliver up the much-loathed, traditional reckoning. Imagine a mother or a father tearing open that envelope, heart-beating, wondering whether this will be an occasion to celebrate with hugs and kisses or glower with frustration or tenderly offer comfort. Slowly, ever so slowly, the white sheet of paper is pulled out from behind it’s protective covering, and the parent looks at the page. Turns it over and looks again. Looks at the child fidgeting, scuffing their shoe against the floor, and gazing in wide-eyed apprehension waiting for their parent to share the news on how he or she has done.

The parent, this term, will see nothing on the page. Aside from attendance and other non-curricular related information, there will be nothing on that piece of paper, except in certain circumstances, because of the job action currently in progress by the province’s teachers.

The parent, this term, will see nothing on the page. Aside from attendance and other non-curricular related information, there will be nothing on that piece of paper, except in certain circumstances, because of the job action currently in progress by the province’s teachers.

The delivery of blank report cards is being sloughed off as a way to minimize the possibility of an outcry from parents — they’re not essential we’re being told, report cards are irrelevant anyways, so don’t worry. But before we consign all those woefully blank sheets of paper to the recycling bin, let’s look at this issue a bit further.

It seems to me that report cards are part of a larger discussion around the issue of assessment which is currently taking place in education. As a parent and active volunteer, I am not very familiar with current practices and research — I can only speak to the information I’ve gleaned through reading, asking questions, and the social media information exchanges I’ve had on-line.

Assessment FOR Learning (AFL) seems to be the approach now being embraced in education circles. This is a process for providing feedback to students — not graded and not numerical — to help them understand where they stand with their learning and the steps they need to take to progress. I think this sounds like a wonderful new approach with lots of potential to create a safer environment for students in which to risk and to strive and to achieve. It also seems designed to help them develop a sense of ownership for their own learning, a critical skill.

However, given the way our society is currently structured, I don’t see how we can escape completely from coming back, at some point, to marking, to a grade, to a numerical value which is presented as a summary of student achievement.

The form and content of a report card still serves a useful function. It provides a snapshot, a quick look at where a student stands at a certain point in time. There may be weaknesses with this approach, but it does actually cover a lot of territory in a relatively quick and efficient way.

To prepare parents for the seemingly absurd — actually, surreal — experience of receiving blank report cards the push has been to assert that teachers will provide information on how students are doing, and so forth. I have no doubt they are endeavouring to do so.

But let’s consider: when report cards are sent home, there will be a certain percentage of parents who request a follow-up with the teacher because of concerns they have regarding their child’s assessment. However, it seems to me that the larger proportion of parents accept the report card without question. Are we cognizant of the additional time commitment on teachers if report cards are eliminated and instead of speaking with only those parents who do follow up, being required to provide assessments by speaking to ALL parents? In speaking today to a Trustee from another provincial jurisdiction there are also those parents who may be hesitant to approach teachers and schools. To them, the report card is the primary means of communication they rely on. While we may want to focus on community outreach to allay such reluctance, maybe we need to be aware that report cards do represent a valid mode of communication for a subset of parents.

I think the focus on assessment is crucial: both the assessment for students in school for their learning and as a means of sharing information with those outside the confines of the classroom and the school. And perhaps there will be better models — maybe there already are — for reporting out and maybe we do have to consider at what age and for which students numerical values or letter grades for performance are appropriate.

Until we get there, let’s not label report cards irrelevant: they aren’t. Let’s focus instead on finding the combination of form and content which will make assessment and reporting meaningful, productive, supportive, and transformative for all students.

Hierarchy And Assessment

The inaugural meeting of the new West Vancouver Board of Education will be held on December 13, 2011. On that date, I’ll be acknowledged as a Trustee and officially launched into my new role and new set of responsibilities.

In the lead up to that ceremony and the official recognition it entails, I also had the pleasure of meeting George Abbott, BC’s Minister of Education during his visit to the District earlier this week.

He met with the new Board for just over an hour for a very interesting, wide-ranging discussion touching on many of the key public education issues we are facing. He was thoughtful, approachable, keen to listen, and showed evidence of his personal commitment to his ministerial portfolio, one he’s held for approximately a year. He’s also got a very natural manner and a ready wit.

Minister Abbott’s visit was highly anticipated and a lot of planning went into making sure the day went smoothly. And while he struck me as very down-to-earth, I’m also aware that all the stops were pulled out for him and his team because of who he is.

In the lingo of our day, he is a Very Important Person.

As I have before, I found myself reflecting about the way we determine status in our society and the relative value of individuals. Think about the way we encourage our children to stand in line for autographs, to revere sports figures, to worship entertainers. In the case of anything related to Disney, those are line-ups for autographs from actors portraying characters. They aren’t real!

It seems to me we cannot escape the fact that we live in a very hierarchical system, one which by its very nature is inherently unfair. There are many inequalities in our society — economic inequality being one which served as the impetus for the Occupy movement — which we may find difficult to accept, which we may want to change, and which we may very well be stuck with for the foreseeable future.

My musing on hierarchy then morphed into thinking about the role of assessment in education. The connection was heightened because I happened to be in the midst of grading papers for the undergraduate course at SFU for which I serve as a Teaching Assistant.

My musing on hierarchy then morphed into thinking about the role of assessment in education. The connection was heightened because I happened to be in the midst of grading papers for the undergraduate course at SFU for which I serve as a Teaching Assistant.

Marking has proven to be the most challenging aspect of the job. I have no trouble discerning which papers are better than others — the quality of the content, the writing style, the technical skill, the way in which ideas and concepts have been distilled and discussed — but attributing a letter grade which will affect a student’s standing in the course and in their academic year is difficult. But I have to do it, I have to give them a mark.

From this experience, I understand more clearly why there is so much discussion — heartfelt, sincere, despairing, dismissive, agonizing — about assessment in elementary and secondary education.

Marks can act as barriers, as obstacles. They judge, they differentiate. They are subjective, they are unfair, they may not reflect the abilities, competencies, talents, and skills of the child. At the same time, are they not completely suited to the way we’ve structured our societal institutions? So, if one makes the argument for the elimination of letter grades, for doing away with academic honours, are we in fact doing a disservice to our students? If they are schooled in an environment which reflects a world we’d like to see — peer-based and egalitarian — do we set them up for disappointment when they are exposed to the world as it is?

It seems to me a chicken and egg situation: do we change education first in order to engineer changes in society or does society have to change first in order for the structure of the educational system to shift?

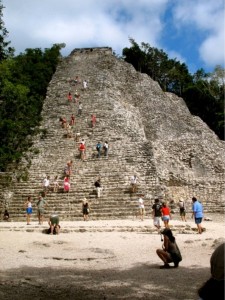

It’s a puzzle I look forward to thinking about and learning about because at the end of the day our goal is to help students achieve the most in their life (which may be defined in many different ways), to climb “to the top” of their potential, even perhaps to be Minister of Education one day.