Posts Tagged ‘writing’

A Life In Script

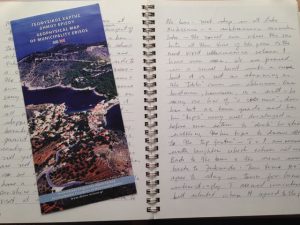

I feel the absence of my mother most keenly when I catch a glimpse of her writing.

When I look at the carefully crafted words and sentences she moulded; the ones she wrote down. An alchemy of thought, energy, effort, pen, and paper.

Mom used writing to express her thanks. To scold political leaders. To extend congratulations. To advocate for causes. To nurture connections.

She cherished the handwritten note even after her grandsons helped her learn to use email.

My mother believed there was a personal quality to a handwritten note that was impossible to replicate in type form. I agree. Each stroke of the pen captures a person’s personality, their character, history, and experience. The way in which hand-written words create a web of meaning is the most affirmative statement of “I am here”. When I catch sight of my mother’s writing script I wonder how it is that she is not here.

How can the person whose heart propelled the pen across the page not be here to cross that t and dot that i?

I feel the absence of my mother most keenly when I see her writing, with an intake of breath and a vise clamped around my heart.

My mother’s script is from an earlier era when education had not been commodified and contorted. When it was a gift to learn. A time when writing was valued not only for its content but for its form. When penmanship spoke of culture and education and, yes, privilege.

That script, her unique cursive style, is undeniably and uniquely my mother, Yulanda.

I feel the absence of my mother most profoundly when I stare at her writing.

René Descartes said, “I am thinking, therefore I am.” My mother’s cursive script says, “I wrote, therefore I have been.” And as the ability to recall her physical presence becomes the dream of time lapsed, her writing will remain forever real and tangible.

As her daughters, her children, and perhaps someday her grandchildren and descendants, we will carry her DNA forward in time. However, her letters, the drafts of her speeches, the thank-you cards, her recipes, the quotations she noted down, her signature — like the one in the volume of William Shakespeare’s collected works that she used for her studies at McGill — these all serve as a testament to her personal spirit.

No other hand shaped those words, no other mind developed those ideas, no one else forged those connections: letter to letter, person to person, heart to heart.

I feel the absence of my mother most keenly when I catch a glimpse of her writing. The words and sentences that flowed from the pen she held, the pen she guided into forever.

In the year and months since my mother died (and a month before what would have been her 79th birthday), my family has cried, laughed, and celebrated birthdays, anniversaries, graduations, and weddings. We’ve attended funerals. We’ve had time at home, we’ve been away together and separately. Time has carried us forward. It is life’s imperative.

And she, my mother, has been there with us. In each moment, in each thought, in each word.

She always will be.

“If we danced more and sang more, we’d be happier people.”

Yulanda M. Faris

July 2, 1937 – April 23, 2015

So You’re a TA, eh?

I’m very pleased to be back at Simon Fraser University (SFU) this term as a Teaching Assistant (TA) with the Department of English. I am leading two tutorial sections for English 104W – “Introduction to Prose Genres: Digital Perspectives on Canada’s Media History and Messaging as a Prose Genre” with Dr. Paul Matthew St. Pierre.

For those of you who follow me on Twitter or on Facebook, you may guess why I’m particularly excited about being a part of this course. Given how much time I currently spend on social media, the course is a way to consider my online practice in a historical and cultural context.

I anticipate that the course content will support what I’m doing, it’ll challenge what I think, and it’ll motivate me to ensure my social media activities are pursued in an even more thoughtful manner. With three lectures done already, I foresee that Dr. St. Pierre may be setting the stage for us to consider our time on social media as “work” within the digital sphere and electronic devices as the tools by which we complete that work.

To think of my time online as work adds a whole new dimension to my role as a digital citizen.

Aside from grounding my social media use in this context, I’m really excited about having the opportunity to work with undergraduate students again.

Why?

It’s not because of the marking, which is likely my least favourite aspect of the job, although assessment is important in the university environment.

It’s not for the office I get to use since it’s remarkable how infrequently students stop by to visit.

It’s not for the authority which the position bestows upon me although it’s wonderful to be able to think about the tutorial sessions as “my classes” and those enrolled as “my students”.

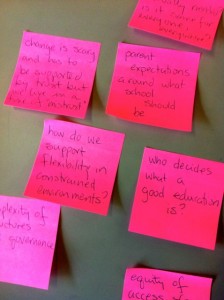

It’s because as I work with the students I feel — I hope — I’m making a contribution to their learning. From exhorting them to look up words in a dictionary, to pushing them to care about writing, to asking them to see beyond the words on the page (or on the screen), I’m trying to show them that they have agency in this world.

I want them to know that their agency will be based on their ability to read, reflect, think, challenge, analyze, and communicate. It doesn’t matter what their career aspirations may be, it doesn’t matter which field of work they intend to pursue, it doesn’t matter what subjects they may wish to study, these are the abilities which will serve them well in any career, in any field, in any subject area.

That is, I want them to value learning, I want them to value thinking, and I want them to know that the ability to fully realize their potential depends on their ability to focus on more than just their grades and to look beyond the message no matter the form.

And in working with them, I recognize that I value my work as a TA because it allows me to do the same with regard to my own agency.

It allows me to recognize the following:

- I’m not so much a person who accepts as I am someone who questions.

- I’m not so much a teacher as I am a student.

- I’m not so much a person who imparts knowledge as I am a learner.

For life.

What’s In A Word?

In 2010, I was accepted into the Graduate Liberal Studies (GLS) program at Simon Fraser University (SFU).

Going back to school, part-time, was one of the best decisions I’ve ever made. In addition to reentering the world of study and immersing myself again in the humanities, my status as a Masters student allowed me to apply for Teaching Assistant (TA) positions at SFU. I’ve been fortunate to serve as a TA in the Department of Humanities for four terms.

I love being a TA. I love attending lectures and brushing up on familiar subjects and topics or delving into new ones. I love the dialogue with students in tutorial — especially on those days when they decide to leap into the discussion — and I love the challenge of trying to figure out how to engage them in texts so that they see how a work that’s centuries old does have relevance to their world today.

And I love playing a role, however small, in helping them develop their writing skills. However, I’m frustrated by the general level of writing I’ve encountered in these courses especially since the participants represent the gamut of undergrad experience, from level one to level five or higher.

It’s more than a question of writing. Although we live in an age of literacy, it seems to me to be a question of reading.

Why?

Because in a world where information is literally at our fingertips, students do not take the time to search out a reference in a literary work or to look up a word.

Because in a world where information is literally at our fingertips, students do not take the time to search out a reference in a literary work or to look up a word.

A simple check in a dictionary app or online could make all the difference in the interpretation of a passage from a primary document or a novel or a philosophical treatise.

A simple Google search can tell you more than you’d ever need to know about a name or time which adds layers of meaning to assessing an author’s intent or understanding a character.

And I find that I can pick out the words which students will most likely not have understood or not have taken the time to investigate, with eerie accuracy, even if they are what I would consider simple words for someone studying at the post-secondary level.

The latest such word was “pious”.

The professor I’m working with this term used the word during his lecture. He was talking about characters or figures who, albeit pious, face serious consequences in their lives. That is, the tragedies with which they contend are not a reflection of their personal morality, but are often a reflection of their time and the socio-cultural values of their societies. That’s a much more sophisticated analysis than saying they were “bad” or “unlucky”.

What’s in a word?

The world is in a word.

A world of meaning is embedded in a word, a world of interpretation, a world of understanding.

Words by the Bee Gees (1968)

You think that I don’t even mean

A single word I say

It’s only words and words are all I have

To take your heart away