Posts Tagged ‘knowledge’

So You’re a TA, eh?

I’m very pleased to be back at Simon Fraser University (SFU) this term as a Teaching Assistant (TA) with the Department of English. I am leading two tutorial sections for English 104W – “Introduction to Prose Genres: Digital Perspectives on Canada’s Media History and Messaging as a Prose Genre” with Dr. Paul Matthew St. Pierre.

For those of you who follow me on Twitter or on Facebook, you may guess why I’m particularly excited about being a part of this course. Given how much time I currently spend on social media, the course is a way to consider my online practice in a historical and cultural context.

I anticipate that the course content will support what I’m doing, it’ll challenge what I think, and it’ll motivate me to ensure my social media activities are pursued in an even more thoughtful manner. With three lectures done already, I foresee that Dr. St. Pierre may be setting the stage for us to consider our time on social media as “work” within the digital sphere and electronic devices as the tools by which we complete that work.

To think of my time online as work adds a whole new dimension to my role as a digital citizen.

Aside from grounding my social media use in this context, I’m really excited about having the opportunity to work with undergraduate students again.

Why?

It’s not because of the marking, which is likely my least favourite aspect of the job, although assessment is important in the university environment.

It’s not for the office I get to use since it’s remarkable how infrequently students stop by to visit.

It’s not for the authority which the position bestows upon me although it’s wonderful to be able to think about the tutorial sessions as “my classes” and those enrolled as “my students”.

It’s because as I work with the students I feel — I hope — I’m making a contribution to their learning. From exhorting them to look up words in a dictionary, to pushing them to care about writing, to asking them to see beyond the words on the page (or on the screen), I’m trying to show them that they have agency in this world.

I want them to know that their agency will be based on their ability to read, reflect, think, challenge, analyze, and communicate. It doesn’t matter what their career aspirations may be, it doesn’t matter which field of work they intend to pursue, it doesn’t matter what subjects they may wish to study, these are the abilities which will serve them well in any career, in any field, in any subject area.

That is, I want them to value learning, I want them to value thinking, and I want them to know that the ability to fully realize their potential depends on their ability to focus on more than just their grades and to look beyond the message no matter the form.

And in working with them, I recognize that I value my work as a TA because it allows me to do the same with regard to my own agency.

It allows me to recognize the following:

- I’m not so much a person who accepts as I am someone who questions.

- I’m not so much a teacher as I am a student.

- I’m not so much a person who imparts knowledge as I am a learner.

For life.

Do I Want To Know?

Ignorance is bliss.

Or so they say.

And as we hurtle through the German countryside, on this train voyage from Berlin to Frankfurt, on the last leg of our summer adventure abroad, I believe it may be true.

Throughout this trip, I’ve had access to wireless connections and have checked my email regularly, followed Facebook postings and Twitter messages, but not to the same extent I do at home.

I haven’t read the newspaper each morning, I haven’t listened to broadcast news, and I haven’t been voraciously consuming the ups and downs of world events, whether trivial or significant. It helps that many of our accommodation spots have not provided access to a television or that we’ve been too busy exploring to watch.

So while I’ve been connected, I haven’t been obsessed and that’s opened room in my thoughts and daily experience to a stronger sense of well-being.

Which is an odd place to be for someone who is an advocate of digesting information regularly, of learning, of being aware that the world is so much more than our immediate circles of influence.

So if ignorance is bliss, why bother with education?

In thinking about this question, I realize how value-laden the field of education is as is the contemplation of what constitutes the qualities of our existence as social beings.

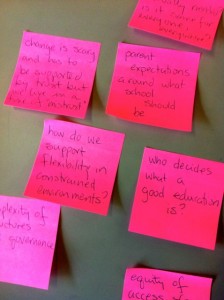

We talk about believing in better, but what’s better?

We talk about the value of knowledge, but what is knowledge?

We talk about leading good lives, but what constitutes a good life?

In addition, as I contemplate the historical record (traveling in Europe seems to make history somehow more real and pressing), I realize that crimes and atrocities, throughout the centuries and in our own day, are or have been committed by well-educated people.

Education has not acted as a barrier to tragedy, war, deprivation, suffering, inequality, and injustice.

And while I have a feeling the key is to keep asking questions rather than settling on fixed answers, there is one conclusion I feel able to draw with some certainty.

The most important result of education is to enable people to become and to be critical thinkers. And while the search for consensus may be integral to making progressive changes (what is progress? why change?), individual voices are needed now more than ever as is tolerance for different points of view.

And that’s a troubling aspect of political life in Canada and elsewhere along with the evolution of our mainstream media systems. It seems the goal is to manipulate citizens into thinking en masse by removing dissension and erasing individuality.

I can’t help feeling that we should – at this point in time and with the lessons of history – know better.

Ignorance may be bliss, but, as my nephew says (he’s recently graduated from the University of Bradford Peace Studies Department) “blissed” ignorance is not just.

Perhaps that’s the ultimate purpose of education then: to establish, maintain, and sustain just societies.

If so, let’s get on with it.